Media accounts of global warming/climate change/climate disruption often explain Americans’ views of climate change in terms of how educated we are. Americans who have extensive schooling and multiple degrees, we are often told, believe climate change is a serious policy problem that requires action by the federal government. Americans who do not think climate change is occurring or an important policy challenge are often portrayed as uneducated (at best) or ignorant (at worst). President Obama appears to share this belief. While encouraging graduating seniors at the University of California, Irvine to help fight climate change, Obama stated earlier this month that “since this is a very educated group, you already know the science.” The President, like many journalists, was assuming that being an educated American leads one to view climate change as a serious problem.

The President’s assumption, however, seems unable to explain why members of Congress, let alone regular Americans, disagree so much about climate change. According to the Congressional Research Service, over ninety percent of Representatives and Senators have college degrees, and a majority of Senators have advanced degrees in law, medicine, and other fields. Since members of Congress are well-educated, and they are divided on climate change, the presumed link between education and climate change is questionable.

If being educated is tantamount to thinking climate change is a serious problem, it seems like degree-holding members of Congress, backed by an increasingly educated American public, would have passed much of the President’s preferred climate change legislation. No major climate bills have passed Congress this session. Instead, President Obama has resorted to enacting much of his climate change agenda (including new regulations on carbon emissions from power plants, announced earlier this month) through the executive bureaucracy and Environmental Protection Agency. This political situation suggests that the connection between education and opinions on climate change needs to be re-examined scientifically.

In scientific terms, many contemporary journalists assume a strong positive correlation between education and views of the seriousness of climate change. This means that they write under the working assumption that as an American’s level of education goes up, he or she will view climate change as a much more important policy problem.

This common belief may have some effect on the partisan rancor surrounding debates on climate change. It’s hard to have a constructive debate on policy when both sides spend much of their time arguing about who is ignorant or who is not. But is this common assumption actually true? Is it actually the case that the more education an American has, the more likely he or she is to believe that climate change is a serious problem that needs corrective action by the American government?

To answer this question, I examined data from the 2010 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES). The 2010 CCES survey asks over fifty thousand respondents the following: “From what you know about global climate change or global warming, which one of the following statements comes closest to your opinion?” Surveyed Americans could respond by saying, “Global climate change has been established as a serious problem, and immediate action is necessary,” “There is enough evidence that climate change is taking place and some action should be taken,” “We don’t know enough about global climate change, and more research is necessary before taking any actions,” “Concern about global climate change is exaggerated. No action is necessary,” or “Global climate change is not occurring; this is not a real issue.”

This question captures opinions about climate change very well. The average American who responded to the survey is approximately halfway between believing that “there is enough evidence that climate change is taking place and some action should be taken” and “we don’t know enough about global climate change, and more research is necessary before taking any actions.” If one breaks down responses by partisanship, however, it is easy to see that Democrats, Independents, and Republicans have very different views on climate change.

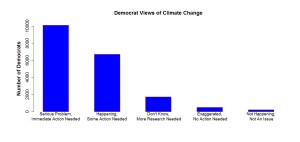

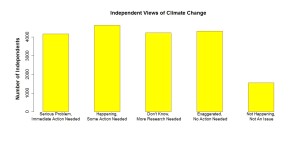

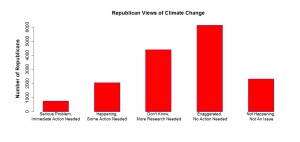

The charts below show Americans’ views of climate change on the 2010 CCES, separated by partisanship.

Democrats want something done about climate change, and they want it done sooner, rather than later. The average Democrat is about halfway between believing that “global climate change has been established as a serious problem, and immediate action is necessary,” and “there is enough evidence that climate change is taking place and some action should be taken.”

Independents have fairly moderate views on climate change. The average Independent is close to the “we don’t know enough about global climate change, more research is necessary before taking any actions” position, with a slight lean toward the idea that climate change is happening.

Republicans generally think global warming is either uncertain or exaggerated, with the average Republican about halfway between these two positions. Republicans believe nothing needs to be done about climate change, especially right now. They’re not concerned about it.

These partisan differences in views of climate change are considerable, though not surprising. Journalists often assume that this variation in views is due to education, and at first glance it seems like they could be right. If one looks at all the people who responded to the 2010 CCES, it appears that as Americans become more educated, they become slightly more likely to view climate change as an important policy problem (the correlation is .09).

In the American public, however, the connection between political actions and opinions and other phenomena often depends on what party someone identifies with. As it turns out, this is true of the relationship between education and opinions on climate change as well. I examined the relationship between education and views of the seriousness of climate change for Democrats, Independents, and Republicans surveyed by the 2010 CCES. For Democrats, level of education and opinions on climate change are modestly related (correlation is .19). The more educated a Democrat is, the more he or she views climate change as a pressing problem that requires government action. This relationship is noticeably stronger among Democrats than it is for all respondents to the 2010 CCES.

Among Independents, the connection between education and climate change opinion is similar to what it is for all Americans on the 2010 CCES. Independents with higher levels of education are slightly more concerned about climate change, but not much (the correlation is .07).

Republicans contrast markedly with Democrats. For Republicans, views of the seriousness of climate change are not related to education (the correlation is -.02). Republicans with MDs, JDs, and PhDs do not think climate change is any more of an important problem than Republicans who have not finished high school. This means that the typical journalist view of the connection between education and opinions on climate change is definitively not true for Republicans.

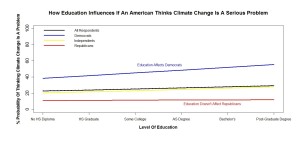

These partisan differences in the relationship between education and views of climate change hold even after accounting for the effects of age, income, race, religion, region of residence, marital status, and ideology. Education modestly influences Democratic views of climate change, has a slight effect on the thoughts of Independents, and has virtually no impact on Republican opinions. The plot below shows the connection between how educated an American is and his or her opinion on climate change for Democrats, Independents, Republicans, and all respondents on the 2010 CCES. This “typical” American’s age, income, race, religion, region of residence, marital status, and ideology (set at the median for the 2010 CCES) do not influence the changes depicted above. Each color-coded line represents how an American’s probability of thinking that “global climate change has been established as a serious problem, and immediate action is necessary” changes as his or her amount of education increases.

Look at the Democrats, represented by the blue line. A “typical” Democrat who has not finished high school has about a thirty-eight percent chance of thinking that climate change is a serious problem. As his or her level of education increases, this probability increases considerably. The same Democrat, but with a post-graduate degree, has about a fifty-five percent chance of viewing climate change as a serious problem. For Independents and all Americans surveyed by the 2010 CCES (the yellow and black lines), becoming more educated has a slight effect on opinions on climate change. “Typical” Independents without a high school diploma have about a twenty percent chance of thinking climate change is a serious problem. Those same Independents, but with a post-graduate degree, have about a twenty-eight percent probability of believing climate change is an important problem that requires immediate action. In contrast, education does not affect Republicans (the red line). Increasing levels of education have no significant effect on whether Republicans view climate change as a serious problem.

Thus, a careful analysis of the connection between education and views of climate change reveals that the conventional wisdom is generally wrong. While education modestly influences Democrats’ opinions on climate change, it has a very slight effect on Independents, and no impact on Republicans at all. Journalists should not assume that Americans who think climate change is an important problem that requires corrective government action are well-educated, while those who do not are ignorant. For most Americans, how educated they are does not explain their views on climate change very well.

Even among Democrats, whose views on climate change are affected by education, the difference between the most and least educated is not large. The primary reasons that Americans have divergent opinions on climate change are partisanship and ideology. The reasons that Republicans don’t think climate change is occurring or important are because they are Republicans and/or conservatives. Though education plays a role, the primary reasons Democrats believe climate change is happening and a serious problem are because they are Democrats and/or liberals. The debate over climate change exists not because one side is educated and the other is ignorant, but because Democrats and Republicans see the world differently.