The Centers for Disease Control recently alerted us to the fact that nearly 40 percent of American adults are now considered obese, up from just over 30 percent in 1999-2000. This alarming news coincided with a tremendous outcry concerning the Food and Drug Administration’s recent delay in implementing a new calorie labeling requirement.

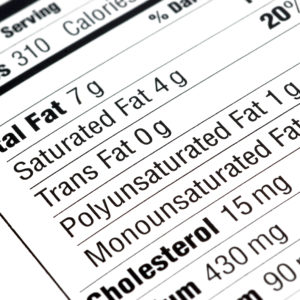

The FDA still intends to update the standard Nutrition Facts Panel (NFP) in the future. But this update, while well-meaning, is a proven failure. Worse, it’s a distraction when we need real solutions.

One activist group previously stated that the delay “harms the public health” and “denies consumers vital information.” Former first lady Michelle Obama likened it at one point to being OK with — and even celebrating — children eating “crap.”

America does have a nutrition problem, but the sentiments expressed above are true only if you believe that the new food label is going to help consumers. It’s not, and the label is still as confusing as ever.

Marie Osmond, in her advertisements for a weight loss program, zeros in on the generic nutrition labeling problem when she notes that the product requires “no measuring, no counting.” She could have added “no tracking.” Because, beyond understanding what such obscure measurements such as the NFP’s “daily values” mean, you would have to do all three to use the NFP successfully.

The problems with diet and health go well beyond the food label. In short, there is too much information, and it is too complex, too contradictory and not individualized.

One survey by the International Life Science Agency found that most people think figuring out what to eat is more difficult than figuring out your taxes. Nutrition research regularly reverses itself as to what foods and nutrients people should be eating. Population-wide recommendations like reducing sodium intake are not helpful for those who do not need to do so.

The bottom line is that it is very hard to discover the right nutrition advice and put it into practice for most people.

For government or the private sector to solve the problem, they need both incentives and solutions. Public pressure certainly provides one incentive — particularly with our obesity problem — but the solutions are lacking. The government response has been to try to get people to change their behavior through labeling, punitive taxation, information campaigns and restricting what people can eat in various government food programs.

None of these have worked. They either require a lot of work for consumers to understand and use (labeling or information), or single out specific foods, ingredients or nutrients through taxes and other restrictions, as though they are responsible for broader nutrition problems. The latter remedy generally ignores the overall diet and the problem of substituting other problem foods for the offending ones.

The private sector hasn’t succeeded either, at least so far. Here, the lure of profits is a stronger incentive than public pressure. Americans spend around $60 billion trying to lose weight on everything from gym memberships to diets. In the United States alone there are more than 100 million people on, essentially, fad diets. There are also huge disease costs associated with all American diets — totaling more than $1 trillion per year in the United States.

Given that consumers do end up paying health costs through direct pays, co-pays, morbidity and premature mortality, the lure for private actors to find actual solutions is enormous. But for now, private sector solutions also fail us: Most diets fail and one estimate finds that 60 percent of gym members never use their membership.

Despite current government and private-sector failures, next generation technologies from the private sector may now present some real solutions.

New innovations in monitoring consumption and health are already showing up. Some will eventually give specific, individualized food recommendations, based on past consumption, exercise, health status, genetics, preferences and even geographical locations (for restaurants).

And we may, in the near future, be able to produce foods that both taste good and fit our nutritional needs through genetic modification.

In short, if solutions won’t come from Washington, they may soon arrive in stores near you.