The zoo that is American politics is primarily occupied by elephants and donkeys. This term, the Supreme Court is looking at a somewhat more rare member of the menagerie–the gerrymander. In two separate cases, Benisek v. Lamone, from Maryland, and Gill v. Whitford, from Wisconsin, the court has been asked to determine if state legislatures redrew district boundaries in order to ensure that their opponents would lose seats in the next election cycle. The Benisek case, which was one of the final cases heard this session, is unusual in that it contests the redistricting on free speech grounds rather than claiming that lines favoring one party over another violate the Equal Protection Clause. The case exposes the complexity of the question of determining district boundaries–a task which brings together questions of geography, demographics, politics, and population–which may not be fully resolved this term.

“The First Amendment framing is not new, but it is unusual,” David Casazza, a litigator who focuses on appellate and administrative law. “Most of these partisan gerrymandering cases, including the other case argued earlier this term, are 14th Amendment cases where the argument is that the line drawing is an equal protection violation, by discriminating in favor of one party over the other.”

Constitutionally, the case argues that the Democratically-held Maryland legislature retaliated against the speech of Republicans in Benisek’s district by redrawing the boundary lines. This is a new framing of the question. Practically speaking, this means that the Court is once again wading into an issue that, until the 1980s, had been considered a political question outside of the hands of the judiciary.

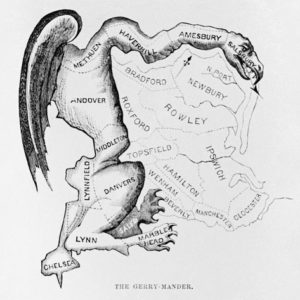

Beneath even the constitutional questions is the matter of what an ideal district should be. Ought districts be determined in order to allow people to live in areas where majority of the population supports the same candidates, or should they be drawn to force the creation of competitive races? Ironically, the quest for competition is likely to force a return to the salamander-like boundaries of the original gerrymander. As Americans increasingly move to live in communities with others who share their political and social beliefs, the task of drawing competitive districts is becoming more difficult.

“There isn’t an impartial way to draw districts,” says Casazza. “There are so many variables to account for when drawing districts. To draw competitive districts you will have to draw some particularly tortured district lines.”

Despite the desire for fairly balance districts, the process of obtaining them is thorny at best. The timing of the gerrymandering litigation–immediately before both a midterm election and an upcoming Census–shows how swiftly the decisions can become outdated.

“[The Court’s decisions] create this perpetual redistricting machine,” says Dr. John C. Eastman, founding director of the Claremont Institute’s Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence. “Here we are in 2018, arguing about what the districts are going to look like for the next election, based on the census that was done in 2010, right before we are going to have a new Census and start the whole process over again.”

Given how slowly these gerrymandering cases progress, it is reasonable to expect the Court not to expand the factors that need to be considered in redistricting cases, says Casazza. Already, these cases are unusual procedurally. After being first heard by a panel of three judges at the District Court level, they can then be appealed directly to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court is mandated to review these cases in a different fashion than standard appeals.

“If the Supreme Court says that partisanship is unconstitutional in redistricting, what they are signing up for is in the next decade, after the next census, they are going to have to have one of these cases before the Supreme Court for all of the over 30 states that have districts drawn by state legislatures,” says Casazza. “And that’s both for congressional districts, for state districts, for school boards, for city wards that are elected by district. This is going to be just an unending torrent of litigation and I’m just not sure that is something there is a huge appetite for on the court.”

This bind is one reason why districting had been considered a political, rather than legal question for so long. Unlike the courts, politicans face the risk of losing their seats if voters are unhappy with how the lines are drawn.

At present, it looks like the Court is unlikely to escape giving some sort of answer to the question of fair districting lines. This term has been bookended by gerrymandering cases. Last fall, the Wisconsin gerrymandering case was the second one the Court heard. It has yet to release a decision for that case, leading some court watchers to speculate that decisions for both cases will come down at the same time.