The societal effects of artificial intelligence (AI) are already being felt everyday by Americans — from the availability of level-three autonomous automobiles to commercial self-adjusting lighting, heating and air-conditioning systems, to Amazon “learning” what your reading preferences are and suggesting books of interest.

These are helpful, if sometimes annoying, conveniences of 21st-century life.

However, AI, the algorithmic codes that are capable of learning and acting based on observed patterns in data sets, possesses a “darker” side.

For example, in a March 2017 report (“The Future of Jobs and Job Training”), Pew Research Center analysts made the following observations on the negative effects of AI:

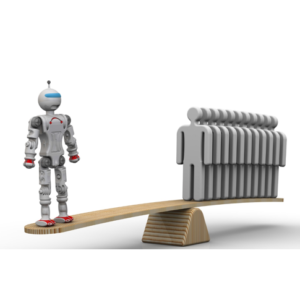

“Automation, robotics, algorithms and artificial intelligence in recent times have shown they can do equal or sometimes even better work than humans who are dermatologists, insurance claims adjusters, lawyers, seismic testers in oil fields, sports journalists and financial reporters, crew members on guided-missile destroyers, hiring managers, psychological testers, retail salespeople, and border patrol agents.

“Moreover, there is growing anxiety that technology developments on the near horizon will crush the jobs of the millions who drive cars and trucks, analyze medical tests and data, perform middle management chores, dispense medicine, trade stocks and evaluate markets, fight on battlefields, perform government functions, and even replace those who program software – that is, the creators of algorithms.”

Genpact, a global professional services firm, released a report (“The Workforce: Staying Ahead of Artificial Intelligence”) based on a survey of 2,795 workers in the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia. The study reports that only 28 percent of workers believe that AI threatens their present vocation, but 58 percent believe that AI threatens the jobs of their children and/or of later generations.

In the United States, however, when workers are asked “How comfortable would you be working with/among robots?”, only 40 percent respond “very comfortable” (13 percent) or “fairly comfortable” (27 percent).

Yet, a September 2016 report (“Why Artificial Intelligence is the Future of Growth”) by Accenture, another global professional services company, forecasts that AI could double annual economic growth rates by 2035 for 12 of the world’s developed economies (including the United States) by creating a new relationship between employee and AI technology.

The company projects that AI would increase labor productivity by up to 40 percent by fundamentally changing the nature of work and reinforcing the role of employees to drive business growth.

So what competencies will employees need to succeed in an AI future? According to Genpact survey respondents, 50 percent believe that “the ability to change” is most important, followed by “critical thinking and problem solving skills” (44 percent), “the ability to think creatively” (42 percent), and “the ability to communicate and collaborate” (40 percent), all outpolling “technical skills (e.g., coding, statistics, applied math” (39 percent).

Likewise, one of the five major themes of future jobs training mentioned in the Pew Report was that “tough-to-teach intangibles, such as emotional intelligence, curiosity, creativity, adaptability, resilience and critical thinking, will be most highly valued.”

According to Northwestern University’s Joel Mokyr, based on the above AI driven changes in the workforce, the corporation of the future will be a much looser network of various flexible, mostly small-scale, units. Moreover, there will be greater fluidity in organizational structures, more redundancies, retraining requirements, and therefore increased need for “knowledge augmentation” or updates.

The business education sector, i.e., colleges and universities, will consequently need to deliver synchronized learning to a dynamic, changing audience. Student populations will move away from discrete learning experiences to those that are continuous, fluid, and applied while learning, almost like having a “lifelong learning companion” instead of a semester. This scenario will involve three broader changes.

First, a vocational approach involving collaboration with industry to inculcate critical thinking in strategic directions, and creativity and adaptability in work projects. Second, hybrid and blended delivery modes, rather than strictly online or offline, since the tough-to-teach intangible skills require face-to-face synchronous interactions along with the flexibility of online delivery modes. Third, an array of shorter programs and “stackable” certifications, with options for re-skilling at advanced levels with changes and updates in the field of knowledge.

Today, an increasing number of prospective students are demanding part-time master’s programs, with shorter (30) credit hour requirements and a narrower professional focus, such as health care management, strategic organizational leadership, and business analytics. In addition, graduate certificate programs are offering employers’ reduced financial investments (and employee time commitment) for re-training.

While AI will likely have a significant effect on certain occupations — including eliminating many — it will also create new opportunities for enhancing service and product quality and establishing new occupations. Yet for effective harnessing of the full potential of AI in the U.S. workplace, it will require a collaborative “open mindedness” on the part of employees, companies and educational institutions to recognize, learn and adapt to this “brave new world.”