Why Tom Steyer’s green-ish strategy failed to make climate change an issue in the midterms.

These could have been Tom Steyer’s midterms. That is to say, he was by far the biggest spender (to the tune of $74 million) in disclosed outside money seeking to influence votes. Steyer’s spending on his NextGen Climate Super PAC supposedly made green groups into a stronger “electoral powerhouse” than ever before.

But Steyer claimed he was going to make climate a key issue for 2014. Polls show voters don’t rank environmental issues anywhere among their top concerns. The election now seems to have very nearly delivered a veto-proof majority for the Keystone pipeline.

If anything, analysts say Tom Steyer and his environmental message were a drag on those he was trying to help.

His personal ambitions and perceived hypocrisy left both Democrats and Republicans questioning his motives.

“I don’t think there’s any way you look at elections and don’t look at it in terms of wins and losses” Steyer said in April.

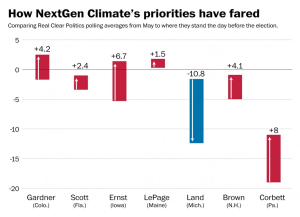

Overall, Steyer notched maybe one “win”—the reelection of Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH). Every other race that NextGen played in was either a win for Republicans (including several upsets) or was expected to be a victory for Democrats regardless of Steyer’s millions.

“Tom Steyer’s impact on the 2014 midterms was not just negligible, he was a net drag on the candidates he endorsed,” said Jeff Bechdel, a spokesman for America Rising PAC, which has frequently criticized Steyer. “After spending more than $50 million, Steyer was unsuccessful by every measure in advancing his radical environmentalist agenda.”

And while Steyer started out making claims he would remain ideologically pure in his support to act on climate change, even suggesting he would go on the attack against Sen. Mary Landrieu (D-LA), he ultimately backed a number of candidates who stood in opposition to his green goals.

Steyer told an audience at Vermont Law School earlier this year: “We have a really good system that has worked really well for centuries. But the question I had was why isn’t this working here? And the answer to me, pure and simple, it’s politics. And that one idea, that one insight is really what’s driven me since then.”

But critics say the game Steyer played has been purely politics as usual. His advertising was deceitful and failed to connect with voters.

Joni Ernst, the newly elected Senator from Iowa, faced some of the toughest attacks from Steyer. David Kochel, a strategist for Ernst, explained why Steyer failed to land any blows against his targets: “Tom Steyer proved why liberals should never be entrusted with so much money. His opening ad, with the laughing tycoons and briefcase was beyond bizarre. They bought into a completely discredited narrative about an Iowa farm girl who truly knows herself and then made herself known to Iowans as one of them. I’ve never seen a campaign with such an off-the-mark approach. It was so completely deceitful, and that’s why it ultimately failed. You can spend a trillion dollars saying the sky is green, but that doesn’t make it true. The cognitive dissonance between his advertising and what people saw and felt about Joni Ernst was the downfall of their effort. But I guess if you’ve got the money to waste, why not waste it.”

While Steyer tried to raise outside money, donors were skeptical because of Steyer’s personal political ambitions. His abandonment of climate politics near the end of the election makes many wonder whether that was really his goal in the first place. Instead, they suggest this billionaire, who made his money investing in fossil fuels, has been trying to launch himself onto the national political stage while blunting attacks faced by others, such as the Koch brothers, by remaking his image as a climate warrior fighting for the planet rather than himself.

InsideSources explores in-depth the impact Steyer had on the 2014 midterms. Our report has uncovered new information about Steyer’s personal climate footprint, tax dodging, and his investments that ultimately funded these attack ads. This report also summarizes the extensive news coverage that has brought to light details of Steyer’s investments. InsideSources spoke with a number of political operatives, who viewed Steyer’s strategy as generally inept, having the opposite of its intended impact. What’s next for Steyer remains to be seen.

Tax Loopholes and a Personal Carbon Footprint

Steyer’s critics believe his personal hypocrisy on energy issues blunted his attacks. Even as NextGen’s ads were over 90% negative against his political opponents, Steyer continued leading a lifestyle counter to his supposed aims. One energy expert interviewed by InsideSources stated that Steyer made his money off energy, leads a lifestyle that consumes excessive amounts of energy, yet he wants to raise energy costs on everyone else.

Steyer stated in a Politico op-ed in July, “[T]he more I learned about the energy and climate problems we currently face, the more I realized I had to change my life.”

While Steyer is calling for others to go green, his personal lifestyle raises significant questions. He’s been known to travel via private jet and gas guzzler. And InsideSources has reviewed Steyer’s property records. He and his wife own five homes together, totaling close to 20,000 square feet. Google Maps satellite images, along with conversations with sources familiar with the homes, reveal that only one of these homes appears to have solar panels. A source, who noted the solar panels on the one home were of an older variety, suggested they may have been installed by the previous owner, Meg Whitman. NextGen Climate did not respond to a request for comment.

Steyer also holds another property, TomKat Ranch, which has extensive equestrian facilities and a posh visitor center for hosting meetings. While Steyer has attacked others for using loopholes to avoid paying a fair share of taxes, a review of records obtained by InsideSources reveals four TomKat parcels are classified as an “ag preserve” under California’s Williamson Act. This allows Steyer to base his tax rate off of the value of the agricultural products of the land rather than the market value of the land. According to San Mateo County parcel information, these four parcels combined are assessed at (and therefore taxed on a value of) $924,659. Without the Williamson Act exemption, these parcels would be assessed at a combined value of $8.6 million. NextGen Climate did not respond to a request for comment.

A Dirty Past

Steyer is worth approximately $1.6 billion. His wealth comes primarily from Farallon Capital Management, a hedge fund he founded in 1986 and where he served as Managing Partner until the end of 2012.

During his time at Farallon, Steyer was responsible for investment decisions. “The discretion to make or break any investment rested with him,” according to a Reuters interview with an anonymous Farallon investor. Another investor said Steyer’s philosophy was to do “whatever it will take to make money.” Steyer’s control of the Farallon portfolio is why many critics have charged him with hypocrisy.

It has been well documented that Steyer earned much of his money by investing in fossil fuels. Steyer invested hundreds of millions from Farallon into coal investments across Asia. The New York Times reported earlier this year that these mines increased their production by 70 million tons a year since Steyer invested. The Times also noted that Steyer’s 2009 investment in an Australian mine set the project on a course to produce up to 13 million tons of coal per year for as much as the next 30 years.

Steyer ultimately divested from fossil fuel holdings, but only after he set the projects in motion and earned a profit.

Who Stood to Benefit from Steyer’s Spending?

Steyer “bristled” when USA Today asked him about comparisons drawn between him and Charles and David Koch, who have spent heavily on elections to drive their libertarian perspective. He said of the Kochs: “What they are doing helps them in a major way. … It helps their economic interests.”

The Kochs defend themselves from such charges, noting that they want government to stay out of the marketplace and not pick winners and losers. If they were actually out for themselves, they would want special favors from government.

Reviews of Steyer’s current investments and his private comments reveal that Steyer is not selfless in his push for green policies. Speaking with environmental activists and policymakers gathered at his home, he was recorded stating that green energy policy presented “a chance to make a lot of money.”

Steyer serves as the primary financial backer of a venture capital firm that focuses on green companies.

History also offers an important understanding of how Steyer has used politics for profit. In the mid-1990’s, Steyer invested in a Colorado aquifier that locals said would ruin the San Luis Valley and take away the water they needed. Farallon pushed ballot initiatives so the fund could cash in sooner.

More recently, Steyer became involved in a dispute with Sen. David Vitter (R-LA). Despite Steyer’s supposed environmental aims in criticizing the Keystone pipeline, Vitter noted that Steyer continued to have a financial stake in Kinder Morgan, which runs rival pipelines. Blocking Keystone stood to be lucrative for Steyer. Once Vitter made the charges that Steyer was seeking to cash in on his political connections, Steyer then announced he would donate any profits he made from Kinder Morgan.

From Russia with Love

Anders Fogh Rasmussen, Secretary-General of NATO, announced at a private meeting in June: “I have met allies who can report that Russia, as part of their sophisticated information and disinformation operations, engaged actively with so-called non-governmental organizations – environmental organizations working against shale gas – to maintain European dependence on imported Russian gas.”

Critics of Steyer do not go so far as to make accusations of nefarious goals, but they actively take note of Steyer’s close connections to Russia, a settlement he reached with the U.S. government over questionable Russian investments, and the profits he’s earned from ties to Putin’s inner circle.

Questions were first raised in the late 1990s and early 2000s about Steyer’s Russian ties. Two American advisers to the Russian government were charged with using their inside knowledge and influence of the Russian economy for profit. Farallon provided the investment vehicle for these profits. Steyer was sent a memo explaining the investment, but he denied having received it. Farallon ultimately reached a $1.5 million settlement but denied wrongdoing.

Before and after the 2014 State of the Union Address, NextGen Climate ran an ad that made the claim: “Chinese government-backed interests have invested thirty billion dollars in Canadian tar sands development. And China just bought one of Canada’s largest producers. They’re counting on the U.S. to approve TransCanada’s pipeline to ship oil through America’s heartland and out to foreign countries like theirs.”

The Washington Post’s Fact Checker gave the ad “Four Pinocchios” for false claims. It is accurate, though, that some oil from Keystone could be shipped to China. And any attempts to block US exports, whether to Europe or China, ultimately benefit Russian interests.

China has been working with Russia to develop oil resources, and last year, the countries reached a deal for Russia to supply China with $270 billion of oil over the next 25 years. Steyer played an important role in developing Russian energy.

In 2008, Farallon purchased a stake in Geotech Oil Services, one of the largest oilfield services companies in Russia, to finance expansion plans, according to a report from the Washington Free Beacon. A decision was made in 2010 by Farallon and other investors to sell part of the company to Russian oligarch Gennady Timchenko, though Farallon maintained an investment in Geotech. Timchenko, now the subject of US sanctions, is part of Putin’s inner circle and is considered a likely source of Putin’s undisclosed wealth. Timchenko sold his shares before being hit by sanctions, but many speculate that the company profited from Timchenko’s favored status in Russia, thus delivering Steyer a big payday.

NextGen Abandons Its Principles

In June, while visiting New York, Steyer told reporters, “We need to reward people whose behavior reduces climate risk and penalize people who add to it.”

The New York Times article that announced the launch of NextGen specifically noted that Steyer was “seeking to pressure federal and state officials to enact climate change measures through a hard-edge campaign of attack ads against governors and lawmakers.”

And Chris Lehane, one of Steyer’s leading strategists, told CNN: “This is the year, in our view, that we are able to demonstrate that you can use climate, you can do it well, you can do it in a smart way, to win political races.” Lehane specifically stated that NextGen would focus on drawing a contrast between “pro-climate action” candidates — and “anti-science” Republicans.

Steyer initially seemed prepared to target Democrat Mary Landrieu (LA), but he ultimately backed away from attacking any Democrats, regardless of whether they supported his climate agenda.

NextGen’s non-profit wing is largely focused on opposition to the Keystone pipeline, but NextGen Super PAC quickly abandoned such tenets. In May, it announced it would back Democrat Bruce Braley in Iowa even though he had voted for a bill supporting Keystone. Braley would go on to lose to Joni Ernst, who faced a barrage of NextGen attacks.

Sen. Mark Udall (D-CO), who also lost, was the beneficiary of NextGen support, but he made remarks supportive of fracking.

In perhaps the only race where Steyer may be able to claim having some influence over the outcome, Sen. Jeanne Shaheen defeated Scott Brown in New Hampshire. Brown tried to attack Shaheen for supporting a carbon tax, but Shaheen’s campaign pushed back on the charge, with Politifact rating Brown’s statements “mostly false.” NextGen’s climate push wasn’t driving Shaheen to take any clear stance on the issue in her campaign.

A review of NextGen ads reveals an overwhelmingly negative tone. Over 90% of federal expenditures were spent on attack ads.

Toward the end of the campaign season, NextGen seemed to hit a hard reality that it could not succeed using climate change as a wedge issue. In polls, climate barely registered as an issue of concern. In late September, Gallup tested 13 issues that may impact the vote this year and found that climate was the least likely to influence the election.

NextGen focused its message particularly on Latinos in Florida. But an October poll of Florida Latino voters found only 4 percent considered climate an important issue.

Political commentators have stated it simply wasn’t important in races across the country. If anything, Republicans gained in close races where climate was made an issue.

Florida Gov. Rick Scott was expected to lose his reelection bid in Florida. NextGen spent nearly $20 million attacking him. But he prevailed on election night.

“The American people don’t care about Tom Steyer’s radical environmental agenda,” said Chris Warren of the Institute for Energy Research. “They care more about issues that impact their livelihood, like whether or not they can afford their next electricity bill. Steyer’s message was absolutely tone deaf, and that’s why his efforts failed and the $74 million he spent this election cycle was wasted.”

While Steyer ran a number of ads that addressed energy, NextGen ultimately seemed to abandon the strategy. An ad that closed out the election in Colorado focused on birth control. It was run by the NARAL Pro-Choice Colorado IE Committee but was funded by $239,000 from NextGen. An attack on Florida Gov. Rick Scott focused on support for the sugar industry, and another concentrated on electric utilities. Other ads tried to tie candidates to the Koch brothers, without much concern for climate issues.

“The fact that he ran ads that had nothing to do with climate change shows that he cares more about influencing elections than engaging in the debate over our nation’s energy policies,” explained IER’s Warren.

Many of the ads from Steyer’s NextGen were criticized by independent reviewers for being false and misleading. Fact checkers called out ads made against Joni Ernst in Iowa, Rick Scott in Florida, Terry Lynn Land in Michigan, and even a state senator in Washington.

Well before the 2014 campaign kicked into high gear, Steyer’s strategy seemed to reveal cracks in its focus on climate. Steyer spent on partisan groups rather than climate. From early on, Steyer was the largest individual donor to both Harry Reid’s Super PAC and the Democratic Governors Association.

“The ‘green’ part of Steyer’s strategy is the money,” explained a GOP strategist. “Everything else was pure politics.”

One campaign strategist in a state targeted by NextGen couldn’t see how the organization was having any impact. Its ground game targeted college campuses, but exit polls in the state ultimately showed Republicans performed better with young voters than previous years.

A number of observers have questioned Steyer’s off-beat ads over the past few months. Independent analysts labeled them “bizarre.” The Washington Post’s Aaron Blake wrote shortly before the election: “If Democrats lose the Senate and some key races where NextGen played come Nov. 4, you can bet that there will be plenty of second-guessing about whether Steyer’s millions were spent in an effective manner.”

Some critics couldn’t even begin to comprehend the “Bananas” video from NextGen that apparently targeted millennials.

Equally odd was the decision by Steyer to invest in some races that would become easy wins for Democrats. NextGen played in the Michigan Senate race, where USA Today reported it built out an operation of 135 canvassers and staffers. Michigan is the only state where the Democrat improved in polling after Steyer announced his involvement. But as most other outside spending was pulled out of Michigan to invest in races where it was needed, Steyer continued investing.

The Pennsylvania Governor’s race was also a win for NextGen, but again, it was a state Republicans expected to lose—and did, by a healthy margin.

What’s Next for NextGen and Steyer?

Some have speculated since the launch of NextGen that Steyer’s plans were more self-interested than he would ever reveal.

In a USA Today interview, Steyer left the door wide open to a potential run for office—under the guise that he would only run to help the climate: “If I thought there was a real reason to run that would move the ball forward, I would do it … But that’s not what we are doing now. … I’m not doing this as a pretext for something else.”

One Democratic donor confided to Politico that Steyer’s ambition to seek office seems to take precedence over climate change.

Steyer aimed to raise $50 million in outside money for NextGen. This is an unbelievably large sum compared to other environmental campaign groups, and ultimately he came up far short, contributing most of the money for NextGen himself. Some top Democrats told Politico that Steyer’s efforts to woo outside donors were nothing more than “self-aggrandizement.”

Whether NextGen lives on after 2014 is unknown. The organization did not respond to requests for comment.

As for Tom Steyer, his interest in politics will most certainly continue. And many predict the billionaire will soon be funding a campaign for himself rather than climate change. Based on what’s been learned of Steyer and NextGen, that campaign is destined for hard-edged attacks from both sides. Charges of hypocrisy and questions over the true beneficiary of Steyer’s politics are sure to continue following the billionaire.

Regardless of whether Steyer’s true aim is to catapult himself into office or impact the debate over climate change, his efforts so far would suggest he is simply tilting at (or for) windmills.

UPDATE: In an interview with the Huffington Post shortly after this story posted, Steyer seemed undeterred by his losses, stating, “I think it was money incredibly well spent.”