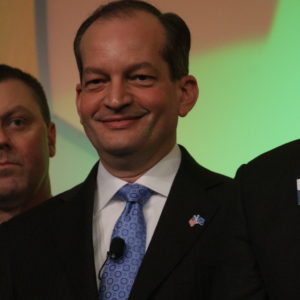

U.S. Secretary of Labor Alexander Acosta visited the State of Iowa this week to deliver the closing remarks to the 2018 Governor’s Future Ready Iowa Summit.

The summit featured a day’s worth of speakers stemming from economists, researchers, economic developers, as well as guest appearances from the governors of Arkansas and Colorado, discussing the importance of not only educating youth, but retraining the adult workforce to take advantage of jobs available in advanced manufacturing and high-skill service careers.

While Acosta commended Governor Kim Reynolds’ efforts in promoting science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) both in the classroom and communities, as well as the administration’s follow through with the Future Ready Iowa Act, he did make his case to the summit of educators, administrators, CEOs, and university personnel that the state still has a hurdle to overcome in the form of occupational licensing reform.

“[The Department] is committed to giving flexibility to the states to administer policies that work for them,” Acosta said. “And we ask that states look at their internal flexibility in return, in the conversation on issues that have to be issues of occupational licensing.”

Acosta said that as it currently stands, nearly 33 percent of Americans need an occupational license to work in certain careers, as compared to 1 out of 20 Americans previously needing an occupational license in the 1950s. According to the Council of State Government-Midwest, 33 percent of Iowa’s workforce is licensed.

“Excessive licensing hurts americans,” Acosta told the sold-out crowd at the summit. “Occupational licensing costs the economy 1.6 million jobs a year, about 1.3 percent of the total employment rate. Now, 1.6 million jobs is hard to translate, but imagine a 1.3 percent reduction in the unemployment rate.”

While Acosta phrased the issue from a national perspective, he did argue directly against Iowa having an unnamed occupational license “to install something” that cost approximately $1,200, which its neighboring states of Wisconsin, South Dakota and Missouri do not require.

Though Acosta only made one direct comment towards Iowa’s mandated occupational licenses, a report last year by non-proft national law firm Institute for Justice, ranked Iowa 12th in the nation for most burdened by occupational licensing. The libertarian firm reports that 71 out of 102 “lower-income” occupations require a license to work in the career. Even though the state ranks 37th in most burdensome licensing laws, it still keeps the 12th ranking for “broadly and onerously licensed state.”

On average, the state’s barriers to entry into a low-income profession are approximately $178 in fees, 288 days lost to education and experience training, and the need to pass one exam to practice. Acosta said that licensing professions that are considered “low income” only hurts those who are trying to make a carrier in these professions, who are often entering the profession because of a lack of money.

According to the Institute for Justice report, Iowa is one of six states that license travel agents, and one of eight states that license dental assistants. For dental assistants, the license program requires 20 hours of education, six months experience (approximately 185 days), $86 in fees, and three exams — 32 states in the nation don’t require anything. Iowa also has some of the strictest requirements for barbers and cosmetologists, requiring 2,100 hours (approximately 490 days) of experience, while Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs) need only 110 hours to become licensed.

Acosta recommended that states like Iowa take three avenues to address the problem: streamline license processes, accept other states’ licensing criteria to make skills translatable across state lines, or to eliminate them entirely.

States like Michigan and Wisconsin recently passed laws that curtail license requirements for careers such as barbers and cosmetologists, allowing people from out of state to translate their skills, and reducing the amount of experience needed. In 2016, the Obama administration allocated $7.5 million to associations to decrease the certain licensing requirements. In terms of other federal attempts to address over-licensing, the HOPE Act, introduced in the House last year would provide additional authority to state governors receiving an existing, bipartisan appropriation of discretionary funds for career and technical education, giving governors more discretion to used the funds for consolidating or eliminating some licenses. The ALLOW Act introduced last year also would have made it so that spouses of military members would be able to transfer their licenses across state lines in order to keep jobs during relocation.