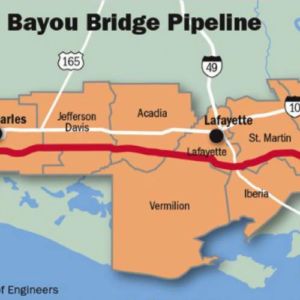

It might seem odd to call pipeline protests a fad, but in some sense, it seems that they were. Although #NoDAPL movement drew thousands of people to camps alongside the Missouri River in 2016, a year later, environmental activists had difficulty rallying public support against additional pipeline construction. For the past year, many of the same activists who protested in North Dakota worked to halt the Bayou Bridge pipeline in Louisiana, to no avail. On December 14, the Army Corps of Engineers issued the final permit necessary for Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) to begin construction of the 162.5-mile crude oil pipeline. Though ETP now has all the permits it is legally required to have, pipeline protesters have vowed to continue to resist construction.

“The Corps neither supports nor opposes this project,” said Col. Michael Clancy, commander of the New Orleans District for the Army Corps of Engineers. “Our mission is to apply the best science, engineering and information available to determine if a proposed project complies with all regulations under our authority.”

The Corps of Engineers permit process required that ETP produce a Coastal Use Permit and a Water Quality Certification, both issued by the state of Louisiana, as well as proof that wetland mitigation requirements had been met. However, Clancy’s remarks show that, even after approval was granted, construction of the pipeline remains a heated topic.

“The state has an obligation to explore better economic opportunities for Louisianans that don’t put our drinking water at risk or destroy our wetlands,” said Alicia Cooke of the New Orleans chapter of the environmentalist group 350.org, who vowed to take action. “The regulators of the state of Louisiana had a chance here to make substantive change to “business as usual,” to put citizens over corporations – instead, they failed us. But ETP has not yet won, nor will they win. Together we are powerful, and together we will continue our peaceful, prayerful resistance.”

Cooke’s statement of protest was seconded by a number of other environmentalists, including representatives from Greenpeace, the Sierra Club, Earthworks, and other groups tied to the NoDAPL protests.

“If Energy Transfer Partners wants to provoke a giant, then that’s what they will get,” said Dallas Goldtooth of the Indigenous Environmental Network, a group which was a strong supporter of last year’s Standing Rock protests. “As we stood against DAPL and demand to keep fossil fuels in the ground, we stand against Bayou Bridge.”

Having failed to stop the pipeline legislatively, environmental activists are moving against it in other ways. Cherri Foytlin, director of the anti-pipeline group Bold Louisiana, recently purchased land in the path of the pipeline. Foytlin made a point of asking permission from the Atakapa-Ishak Nation, whose ancestral homelands include the property.

Foytlin intends to use the parcel as another means of resisting pipeline construction. However, her ability to prevent the company from using eminent domain for the pipeline project is uncertain.

Meanwhile, No Bayou Bridge is organizing a resistance camp, which they call L’Eau est la Vie, French for “water is life.” Unlike the Standing Rock protest camp, L’Eau est la Vie is more formally organized. Instead of merely showing up, the indigenous-led camp requires that they be first vetted. The vetting process claims to include a written application, a phone interview, and both webinar and in-person training on topics including swamp survival skills, anti-oppression, and “direct action.” The application asks potential protesters if they have participated in resistance camps before, have received direct action training, or have previous organizing experience.

The application suggests that L’Eau est la Vie is not intended to grow to the size of Sacred Stones, where more than 10,000 protesters gathered in the summer of 2016.

“Even if you are accepted to camp, that does not grant you permission to come at anytime,” the form warns.

Protests against the Bayou Bridge pipeline lasted for the better part of a year. Led by several different groups, including Bold Louisiana and the Louisiana Bucket Brigade protesters interrupted hearings by the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources, built a short-lived protest camp, and gathered thousands of signatures in an attempt to force the Army Corps of Engineers to conduct a full environmental impact survey.

Their efforts were supported by Louisiana Congressman Cedric Richmond (D), who wrote a letter in May requesting that the Corps complete the environmental impact survey. Such a survey could take years to complete, a wait that could kill the project outright.

While ETP has cleared most regulatory hurdles, a spokesperson explained that it must still obtain a permit from the Atchafalaya Levee District and approval from the Coastal Protection Restoration Authority. Meanwhile, protesters are stepping up lawsuits against the company.

Harry Joseph, pastor of the Mount Triumph Baptist Church in St. James, Louisiana, outside of New Orleans, joined a lawsuit arguing that the state department of natural resources did not adequately consider the potential health impacts of spills for area residents. They argue that the presence of the Bayou Bridge pipeline will block an evacuation route.

In addition, the protesters are pressuring the state of Louisiana not to grant private security firm Tiger Swan a permit to operate in the state. Tiger Swan provided security at the DAPL construction and protest sites and protesters argue that the company used excessive force. Louisiana denied the company a permit, but Tiger Swan has said that it is appealing the decision.

Environmentalists are also going after Governor John Bel Edwards’ office, suing for records related to the Bayou Bridge pipeline proposal. Represented by the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), the Louisiana Bucket Brigade is suing for state records showing Bel Edwards’ appointments earlier this year. The group wants to determine to determine who Bel Edwards and his office spoke to from the pipeline company. Pipeline opponents allege that Bel Edwards refused to meet with environmental groups.

When completed the Bayou Bridge pipeline will carry oil from terminal hub facilities in Nederland, Texas, to terminal facilities and refineries in Lake Charles, Louisiana.

CORRECTION: This piece was edited to clarify that the Atchafalaya Basinkeeper was not involved in direct action protesting.