More and more frequently, we hear of mega-size donations to charity by the wealthiest people in our society. We’re especially likely to see them around this time of year, as the season of giving really gets underway.

From Bill Gates to Jeff Bezos to Mark Zuckerberg, Forbes magazine’s list of the country’s 400 richest billionaires is full of stories of their nearly unfathomable charitable largesse.

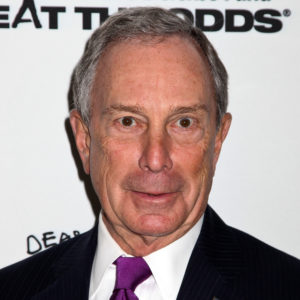

The latest entry into this field, Michael Bloomberg, just announced a $1.8 billion donation to his alma mater, Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins University.

There are many reasons to celebrate these acts of sharing: Bloomberg’s gift will allow many more people to attend that university without massive debt. But the increasing frequency of gifts of enormous size comes with its perils.

Our society is growing more and more unequal. Over the past couple of decades, we’ve seen declining security for the majority of the population, and vast increases in wealth for those at the top. The 400 wealthiest billionaires in the United States now have wealth equal to the assets of the bottom two-thirds of U.S. households combined.

And as our economy becomes more top-heavy, so does philanthropy.

Small-dollar donor populations are shrinking, while major donors and mega-donors are increasingly altering the nature of the nonprofit sector. They’re creating vast reservoirs of largely unaccountable capital, just as they’ve done on Wall Street.

Those were some of our findings in Gilded Giving 2018, a new report for the Institute for Policy Studies. Giving by low- and middle-income donors, we found, has been in a steady decline for almost two decades. All charitable revenue growth during that time has been entirely due to increased giving by the very wealthy.

Undoubtedly, giving from the wealthiest in our society comes from a genuine wish to do good. But it also gives us pause, for several reasons.

First, the independent sector is strongest when it has a wide variety of stakeholders. Top-heavy giving puts the nonprofit sector at risk, because it means charities and nonprofits increasingly have to cater to the preferences of wealthy donors.

Another concern is that the wealthy tend to give through vehicles that encourage the warehousing of charitable revenue.

Nearly two-thirds of the charitable giving from the 50 largest donors in the United States goes into private foundations and donor-advised funds. These instruments give donors an immediate tax deduction for their gifts, but can allow funds to sit for years — and sometimes forever — before being granted out to active charities serving real needs.

Perhaps the greatest danger is that some mega-donors use charity as a tax-avoidance strategy.

As taxpayers, we subsidize tax deductions for charitable giving, chipping in 37 to 57 cents for every dollar that goes to charity to make up for lost tax revenue. That gives us a stake in ensuring that the public interest is served by any gift —particularly those of enormous size.

But if money is warehoused for years in private foundations and funds, it’s not serving public needs. And a high percentage of donations from the wealthy are in the form of appreciated assets, such as art and real estate, which allow for easy abuses of the deduction.

Charity is great for building hospital wings, funding art exhibits, or keeping university departments afloat. But even massive gifts like Bloomberg’s are no substitute for the wealthiest paying their fair share of taxes to support the public services we all rely on.

We must reform the rules governing philanthropy to encourage more broad-based participation and to reduce the risks of top-heavy, tax-avoidance giving. Expanding the universal deduction, for example, would give the rest of us the same tax advantages the wealthy already receive for their gifts.

Anti-warehousing provisions — such as requiring private donation vehicles to actually donate their holdings in a certain period of time, or requiring foundations to spend down — would ensure that charitable funds are actually getting to the communities they’re supposed to serve in a timely way.

Major giving requires major accountability — both to make sure it serves the public it’s designed to serve, and to ensure it doesn’t replace social services that don’t rely on the generosity of billionaires.