This week, House Republicans plan to move ahead on their quick-paced march toward enacting the American Health Care Act (AHCA), their partial repeal and even–less-partial replacement of Obamacare. Outward appearances of dissent within their ranks, and discordant messaging between the GOP-controlled House, Senate, and White House are real. In the final analysis, they may be beside the point of political imperatives.

After nearly eight years of opposing and resisting the Affordable Care Act (ACA), then promising to repeal that law and maybe even replace some of it, Republican officeholders are on the clock, in “put up or shut up” mode. Their leaders increasingly have little room in which to maneuver.

Speed Limits & Caution Signs

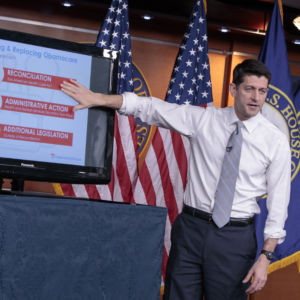

Republican ambitions are severely limited by complicated legislative processes, narrow congressional majorities, and a tight calendar. Converting past rhetorical opposition to Obamacare into a more consistent, appealing, and workable program to replace it remains difficult. Vested interests that have accommodated, if not supported, the ACA now must be disrupted, placated, or threatened to various degrees. Overcoming embedded expectations for continuation of the latter’s subsidies and operational ground rules requires transitional finesse, political patience, and nuanced implementation of new policies. Republican challenges to Obamacare also must overcome deeper baseline assumptions of expanded insurance coverage, increased health care spending, and newer distortions of health care prices, compared to eight years ago. Getting from there to somewhere else will be slower than quicker, and later than sooner, at best.

Sticky Policy Points

Republican Hill leaders began 2017 with more ambition and optimism than their legacy policy proposals and current political support could sustain under heightened stress testing. Four particular areas stand out as needing further re-examination.

Tax Subsidies for Insurance: Mainstream Republican proposals have relied on switching to flatter, fixed-dollar amounts of refundable tax credits that are only moderately adjusted for age. Republican leaders also hoped to extend their relatively less-generous tax credit assistance to many individual insurance market purchasers somewhat further up the income ladder, and then help finance this through more transparent ceilings on the tax exclusion for the most expensive tier of employer-based health insurance plans.

Bottom line: These proposals overstate the drawbacks (work disincentives, administrative complexity) of the more income-related, insurance-premium subsidies under the ACA. Addressing insurance affordability and access needs will require relatively greater assistance to lower income Americans and less to upper income ones. But trying to spread subsidies around to even more people means that those most in need will get subsidized less. Nevertheless, political calculations point in a different direction. Both the ACA’s Cadillac excise tax on high-cost employer plans and Republican tax exclusion cap substitutes are politically dead on a bipartisan basis (though technically just delayed further into the future). Congressional Republicans place greater importance on rewarding more of their voters with new individual market subsidies than with ensuring their relative adequacy for lower income individuals who benefitted more from ACA subsidies. The larger body politic may think otherwise, but different compromise alternatives remain relatively unexplored.

Medicaid’s Expansion: Hill Republicans accurately criticize both the ACA-expanded version of Medicaid and the program’s older components for costing too much, operating inefficiently, and providing inadequate health care to tens of millions of low-income Americans. However, their proposed reform involving per capita caps on future state Medicaid spending faces substantial resistance from Republican governors and senators whose states have chosen to adopt the ACA expansion and try to spend more of other people’s money before it runs out. This approach also remains primarily budget-driven while overstating the possible efficiencies from passing the buck to states to do the dirty work.

Bottom line: Necessary budgetary savings will have to arrive much later here, to close the political deals with Republicans who would rather provide expanded amounts of poorly designed and inadequately reimbursed versions of health coverage of low-income Americans rather than target better versions to the most-needy ones. More creative and structurally significant reforms must extend beyond the confines of simplistic coverage metrics alone and focus more on fostering greater economic mobility, improved health behavior, and more diversified investments in better health outcomes.

Pre-Existing Condition Protection: Republican leaders argue that they offer a different means to the same ACA-prescribed end of ensuring that individuals with potentially expensive health conditions are not singled out for exclusions from coverage, or charged (much) higher premiums, in the individual market. However, they have recently inched away from reliance on stronger incentives to maintain continuous coverage in order to gain and retain this protection. A previous proposal exposed individuals who fail to do so with the risk of paying significantly higher premiums above standard rates and then relied primarily on high-risk pool protection to cap that exposure. The most recent version of House legislation provides a broader guarantee of access to individual insurance regardless of personal health status, with only a one-time penalty charge of 30-percent of standard rates – whenever individuals with a break in coverage decide to return to the market, no matter how long they remain without insurance. The House bill also strongly signals that the most likely option to be followed by states will be a default federal reinsurance program that won’t require them to provide matching funds to gain “innovation” grants to assist high-risk, uninsured constituents.

Bottom line: These weaker incentives to maintain continuous coverage may encourage more adverse selection and less enrollment of healthier risks in the individual market, but they are easier to sell politically in the near term. Even private insurers prefer them, compared to a return to more aggressive risk rating.

Draining the Pay-For Revenue Pool: Longstanding Republican promises to repeal all of the ACA’s taxes (mostly a combination of implicit kickbacks from health industry sectors expecting increased business from expanded coverage; plus double-counted Medicare tax hikes on wealthier individuals) are redeemed in the pending House bill. However, along with the imminent demise of caps on tax advantages for the most expensive employer-based insurance plans, this puts a greater fiscal squeeze on financing the latest version of subsidies for coverage in the individual market and through Medicaid.

Bottom Line: Budget deficits may not matter as much as they did back in 2009-2010, but the limits of the budget reconciliation process ahead will apply greater pressure to produce larger baseline savings in Medicaid, limit tax subsidies for individual market insurance, or resort to more contorted budgetary fictions. Hill Republicans have little appetite for replacing old taxes with new ones, but they may gain less political credit than they expected for repealing the former.

Still No Viable Alternative to Declaring (something) Victory

Despite the above, far-from promising policy and political landscape, the political imperative for congressional Republican leaders and their uneasy followers remains to enact into law whatever will pass both house of Congress, by any means necessary, and then call it Repeal and Replace of Obamacare. They have about six more weeks to do so. Every procedural trick in the book and the full elasticities of modern political vocabulary will be considered as needed. Substantive rethinking of actual policy is too steep a hill a climb at this late date.

However, desperation to avoid worse outcomes in future elections does have a special ability to concentrate the minds of members and loosen their previous stances. So when the last-needed member’s vote climbs on the final train leaving the station, don’t look too closely at the final product. Like a Monet painting, health policy laws tend to look worse the closer you get to them. Even if the “H” in AHCA starts to sound mostly silent.