Our COVID-19 panic attack has resulted in 30 million jobs lost, no clear answer for where to get good medical advice — and has pushed us closer to a looming fiscal cliff.

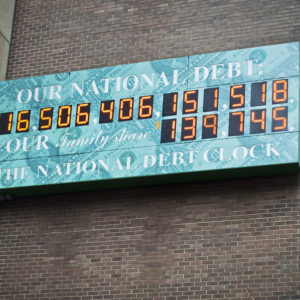

Following the largest round of stimulus payments in history, the Congressional Budget Office predicts a nearly $4 trillion deficit for 2020, bringing the federal debt to more than $26 trillion. If we paid $1,000 every second toward the debt, it would take more than 800 years to pay it off. The numbers are so large that even the analogies start to require analogies.

And so we have Deficit Day.

Imagine the government received all the taxes it intended to collect for the year in one lump sum on January 1, and then started spending what it intended to spend for the year at a constant rate. The money would run out on Deficit Day.

This year, Deficit Day is June 21, meaning that more than half of 2020’s federal spending goes on the government’s credit card. This isn’t unprecedented, but the precedent isn’t comforting. The last time Deficit Day fell this early was in 1944.

We leave it to epidemiologists to say what might have happened had governors not put their states on house arrest, but we can speak to the dire financial straits we are in as a result, which are far worse than they were at the end of World War II.

And whereas that war ended and spending dropped to pre-war levels, there is reason to suspect that today’s multi-trillion-dollar deficits will become the new normal.

Before 2008, Washington spent about 14 percent more than it collected in tax revenues each year, causing Deficit Day to land around mid-November. From 2009 to 2019, that number grew to more than 30 percent, pulling Deficit Day back into October. This year, the government is on track to spend 110 percent more than it collects, resulting in a June Deficit Day.

And where does all that money come from?

The Federal Reserve just creates it, as if that would never cause a problem of any kind. But financing deficits through quantitative easings will eventually spur inflation, leaving the Fed facing a hard choice. It can continue to finance federal borrowing, thereby giving inflation free rein, or it can control inflation by raising interest rates, thereby increasing the interest expense on the debt.

And with a debt of $26 trillion, each percentage point increase in interest rates costs the government another quarter of a trillion dollars annually.

Politicians have no one to blame but themselves for spending us into this hole. And voters have no one to blame but themselves for allowing politicians to get away with it.

If federal spending returns to normal in 2021, we could achieve a balanced budget if Washington froze federal spending for almost a decade. If, thereafter, Congress limited spending growth to match economic growth, it would take an additional 50 years to pay off the debt. And this doesn’t include unfunded Social Security and Medicare obligations. Covering those would take a century or more.

But federal spending won’t return to normal, and the government won’t hold spending constant for a decade. The government is on track to spend $7 trillion this year.

Given what happened after the 2008 crash, that spigot will likely never be turned off, and with this new spending we have finally painted ourselves into a corner. Everyone is blameworthy — from the presidents who propose budgets to Congresses that pass them to the American people who want to get more and pay less.

And now, the Federal Reserve is running out of options. As the Fed magics money into existence to cover Washington’s profligate spending, inflation will follow. And there will be nothing anyone can do about it when it comes.

Happy Deficit Day, America.