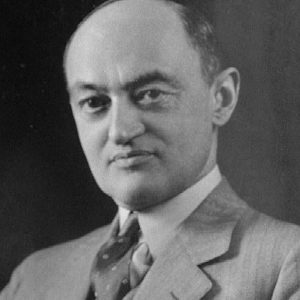

When Joseph Schumpeter died 70 years ago, on January 8, he still had a lot to say. His nearly indecipherable notes on the history of economic thought were spread around two residences and his office, to be eventually painstakingly pulled together by his dedicated economist wife, Elizabeth, as she fought her own terminal cancer. The posthumous 1954 “History of Economic Analysis” has never been surpassed in scope or wisdom.

But most of what Schumpeter still had to say was about the future, not the past. He is best known for his “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy” — the final edition appeared in Schumpeter’s final year, 1950. The central message is that innovation is the key to human betterment, and most dramatically betters the lives of the least well-off.

On the 100th anniversary of Schumpeter’s (and John Maynard Keynes’) birth, management guru Peter Drucker penned a famous Forbes cover story saying that Schumpeter’s key contribution was to ask the right question. Keynes’ main question during the Great Depression had been how to return to equilibrium. In contrast, Schumpeter’s right question was how innovation moves us away from equilibrium toward better lives.

Schumpeter saw innovation as the “creative destruction” of old goods and processes by new goods and processes. He struggled, not always successfully, to understand how creative destruction worked. One failure was his view that innovations must arrive in periodic waves. A major success was his view that the main agent of creative destruction is the innovative entrepreneur.

Economist Richard Langlois has shown us that throughout his career Schumpeter was conflicted on whether this innovative entrepreneur would ever become obsolete — whether innovation could be made routine. In the days before he died, Schumpeter was preparing notes for lectures that he planned to deliver at the University of Chicago. In these notes, Schumpeter’s last words on entrepreneurs are that the future cannot be well-forecast because the future depends on “the emergence of exceptional individuals.” Schumpeter’s last words emphasize the continuing importance of innovative entrepreneurs.

His last words still matter. If we want to stay on the path toward longer and better lives, we must allow exceptional entrepreneurs to emerge, and we must allow them to create exceptional innovations.