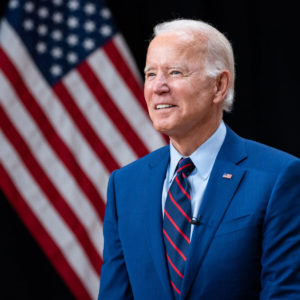

Last week not only saw the inauguration of the 46th President of the United States, it quickly became the week where the new president got right to work overturning existing U. S. government policies. The exact legal instrument President Biden used to make things happen in his first days in office is an executive order.

An executive order is in writing, signed by the president of the United States, and published as a directive from the chief executive. One way to imagine its effect is to think of a company-wide email from the CEO. “Hi, everyone. Here’s our new policy on TPS reports. It’s effective today, Thanks.”

Five words – “Rescind Keystone XL pipeline permit” – garnered global attention as one of the actions President Biden took on his first day in office.

In what many experts predict will be at least a 10-day executive order blitz, President Biden has rejoined the Paris climate agreement, ended the current restriction on immigration to the United States from some Muslim-majority countries, and made mask-wearing mandatory on federal property and during interstate travel.

So, what is an executive order and how does it differ from other forms of decision-making in the federal government processes?

Presidents have used executive orders to get things done for many years. Before the 1900s, it was an infrequently used tool. It is also a tool that can be balanced out by Federal courts and by Congress. Both have the ability to veto executive orders that go beyond the scope of what a president is authorized to actually do.

The most important thing to realize about an executive order – and something that will frame all of the executive orders we see from President Biden over the coming days – is that they cannot create new presidential powers. It is the exact opposite, actually. An executive order is a way for the president to use a power already assigned to them.

The source of that power is Article II of the Constitution. Article II, ratified in 1788, makes the President of the United States the commander-in-chief, the head of state, the chief law enforcement officer, and the head of the executive branch of government (the others of course being the legislative and judicial branches).

While it is true that Congress possesses some power to help shape what a president must do to exercise the authority of the executive branch, the Constitution limits the ability of Congress to essentially micromanage the ability of the president to enforce laws and make other permissible decisions. So those who observe tension between the branches of government where a president does what is permitted by the nature of the office – including the issuance of executive orders – are correct because the Constitution wanted there to be some elasticity and pull-back in the functional nature of these relationships

Article II intentionally gives the president broad powers to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed,” and as the head of state, an executive order can be seen as a type of connective tissue between all of the roles of the president.

What an executive order does better than anything else is enact change where a president sees a real sense of urgency to do so. All an executive order requires is the order itself and the president’s signature, which is why it is going to be President Biden’s go-to in the first days and weeks of his administration.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt is the president who enacted the most executive orders, with a whopping 3,721. Woodrow Wilson sits in second place with 1,803 orders. No president in the past 50 years has exceeded 400 executive orders, with President Ronald Reagan leading the way with 381. While many perceived that President Obama issued many executive orders, over nine calendar years he issued a mere 276 orders, exceeding 40 orders in only 2016.