The 2018 Iowa gubernatorial race could stand to be one of the most expensive races on record in the state as Iowa Ethics and Campaign Disclosure data shows approximately $11 million raised in total campaign contributions in 2017 for the race. This breaks the previous record in 2005, when $5 million was raised in a race that saw Chet Culver win the Democratic nomination, and ultimately the victory over Republican Jim Nussle in 2006.

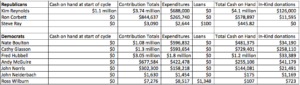

Incumbent Republican Kim Reynolds had the largest amount of cash on hand at the end of the 2017 funding cycle, with a total of approximately $4.1 million, followed by Democratic challenger Fred Hubbell, at approximately $1.2 million. The next closest candidates are Republican Ron Corbett, Democrat Cathy Glasson, and Democrat Nate Boulton. This campaign data doesn’t include in-and-out of state contributions made in 2018.

Iowa Governor campaign finance numbers from both the Iowa Republican and Democratic Parties. Numbers are approximate and include in-and-out-of-state funding through the 2017 filing cycle, not including January 2018.

At the upper echelon of donation receipts is Reynolds, who received approximately $3.74 million, followed by Hubbell at approximately $3.05 million, Glasson at $1.3 million, and Boulton, at approximately $1.08 million. In total, the number of candidates sitting with six figures or more in cash on hand is seven.

“It is incredible that they have raised so much money before the election year,” said Assistant Professor of Political Science at Iowa State University Dave Andersen. “The election year hasn’t really kicked off yet and they have a tremendous amount of money. Even the candidates who have six figures, if you go to any other election cycle, that would make them competitive.”

The Democrats

Andersen said that the Democratic race for the nomination is “interesting” because five of the candidates sit at a minimum of six figures in cash on hand, making them viable for a state-wide campaign, especially since the heat of campaign funding doesn’t come until around April, before the June primary.

Anderson says Democrats must be concerned about the uphill climb they will face against Reynolds’ massive war chest–thinking that may play a factor in deciding the party’s nominee.

One surprising aspect of the 2018 gubernatorial election is the sudden rise of Glasson, a progressive candidate who amassed over $1 million in contributions over the reporting cycle, with more on the way in out of state contributions for the month of January 2018. Andersen said that Glasson “appears” to fit in with the energy that Bernie Sanders brought to the 2016 Democratic Primaries, and supports a progressive agenda, which Andersen said he “hadn’t really heard of before,” in the state. Our Revolution, one of the largest progressive groups in the nation formed in 2016 to carry on the work of Senator Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign, announced its endorsement for Glasson last week.

However, Glasson will have to endure a campaign season full of seven candidates, all wanting the same thing. Andersen said that the fact that so many Democrats are viable in the election, while appearing to energize the base, will ultimately hurt the party in the election.

“In the short run, it’s good for the Democratic Party because with so many different voices coming from all different regions of the state, it’s likely that the individual candidates will resonate more,” Andersen said. “So it makes the Democratic Party look more vibrant and active. But unfortunately, they’re going to wind up angry at a lot of those people because not everyone can win. And the Independents, who really split the difference between Democrats and Republicans in the state, they’re going to hear a lot of negative messages about Democratic candidates, even the one who winds up winning, and they will hold that against them come the November election.”

The Republicans

Andersen said that that the results of Reynolds’ fundraising are in line with expectations for an incumbent. The numbers from in-and-out of state show she has the funding support from establishment Republicans from across the nation that want to see her hold onto the seat. Having approximately $4.1 million at this stage of the campaign has her in a strong position, Andersen said.

While Andersen noted that the Reynolds campaign has the makings of taking the nomination, he also exercised caution about overlooking Corbett in the race.

“Kim Reynolds winds up being very interesting,” Andersen said. “The last poll I’ve seen, is Ann Selzer did a poll in December [2017], that showed that Kim Reynolds’ approval rating is like 51 percent, which sounds great and yet, something like 60 percent of people would prefer someone else to be governor. That’s really hard to reconcile. It suggests people of Iowa like Kim just fine. The people think she’s a fine governor, but they’re willing to entertain other options, and that’s where Corbett comes in.”

Corbett was the mayor of Cedar Rapids from 2010 through 2012, and prior to that, served in the Iowa House of Representatives for seven terms beginning in 1986, and was Speaker of the House from 1995 through 1999.

“[Corbett’s] got a strong center of support from Cedar Rapids,” Andersen said. “They like him there, and he’s put together enough money that he’s going to be a viable candidate and have a statewide campaign, and a good chunk of the population doesn’t know him yet. So he could put together a campaign and derail Reynolds, even though she has a huge amount of money and she’s relatively popular and she’s the sitting governor.”

Andersen said that the ability of Corbett to run a campaign where no one really has a firm grasp of his political identity could help him with the funds he has been able to amass, and could prove challenging for Reynolds to simply run attack ads.

Things to watch

Andersen said that while there’s a notion that money can “buy” elections, it doesn’t in practice. He pointed to the Alabama Senate race last year in which Republican Roy Moore was defeated by Democrat Doug Jones. Andersen noted that there was a lot of money poured into the Moore campaign, but that in the end, the parties have to nominate a candidate who can win.

Andersen did say that money creates a “better situation” for candidates, as it allows campaigns the funding to perform damage control on negative press, and more funding to highlight positive positions.

“The thing to watch right now,” Andersen said, “is the number of people who don’t have an opinion on candidates, and as those numbers go down, that’s a sign that someone’s campaign advertising is really sinking in with the population. The real key is to see how much of that goes into a favorable opinion of a particular candidate.”

Andersen pointed to Corbett’s campaign financing as a campaign that won’t likely have to use it’s money on controlling damage as not much is known about him, which allocates more money to positive usage. He said that if Corbett can inform the “six out of 10 Iowans who don’t know who is,” he stands a chance to beat Reynolds.

As to the Democratic race and the possible divide between grassroots campaigns and party politics — more notably Hubbell’s stature as a wealthy businessman and donor, and the other candidates’ grassroots efforts, Andersen continued that while money doesn’t buy elections, it garners support from the party.

“It has become much more common in this age in politics as elections become more expensive,” Andersen said. “You get these billionaires who are able to self-fund the beginning of their campaign, and the national party loves them, because the national party is looking to win as many seats as they can. And if they can find an area where a candidate is competitive, even if they’re not the most competitive, but they’re competitive and they can fund the race themselves, it saves the national party millions of dollars that they would of otherwise has to invest. So the national party has a real buy in with candidates like this [Hubbell].”