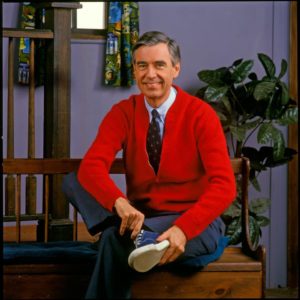

Just in time for the holiday season, moviegoers are being treated to “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood,” starring Tom Hanks as the late, great Fred Rogers. Meanwhile, HBO’s “Won’t You Be My Neighbor” is the highest-grossing biographical documentary of all time. Neither should surprise anyone who remembers the kind, gentle Mister Rogers helping millions of children handle their childhood fears.

Rogers liked everyone “just the way you are,” but there were some adults he didn’t like: the ones children needed protection from. Some of these he called “ever-ready molders of their world.” These are the people who try to instill fear in us, particularly fear and distrust of others. They not only make life unpleasant, they can also undermine the everyday interactions that a healthy country and economy need. Here’s how:

Bruce Yandle—an emeritus dean with Clemson University and a man not unlike Fred Rogers—says, “Practically all market transactions are based on some degree of trust.” Whether buying gas from 7-Eleven or food from a TESCO superstore in Prague, we do so “without a second’s concern about their safety.”

That’s because we have an implicit trust that enables us to transact with one another without written contracts for every single aspect of every interaction. Without trust, according to Yandle, people “could never afford enough police and regulators to induce honest behavior among ordinary people.” Historian Geoffrey Hosking equated trust and distrust to “the basic texture of life” in an economy.

Regardless, the “they’re out to get you” crowd stokes paranoia to get you to distrust others. One way to do this is by applying the adjective “big” in front of a sector like “big food,” “big banks,” or, more generally, “big corporations” as if they’re all the same. Some encourage us not to trust doctors, mechanics and, of course, government. (Oddly, when people trust government less, we sometimes see more regulation.)

Are these businesses or institutions above sensible criticism? Of course not. But each generally succeeds by pleasing as many people as possible, not by seizing every opportunity to betray our trust.

Millennials and Gen Z have lower levels of trust than the rest of us. And unfortunately, many were too young to see “Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood,” which ended in 2001. According to a Harvard University Poll, they don’t trust the media (88 percent), Wall Street (86 percent) or the federal government (74 percent).

When taken to its extreme, distrust can help destroy a country. Hosking looks to the former Soviet Union: “When distrust takes over, it does so rapidly and cumulatively, and can be extremely destructive in its effects.” Stalin’s “witch-hunting” campaigns destroyed trust and, in the process, churches, families and property. Decades later, Russia still ranks among the last in the world for institutional trust.

Distrust in America is nowhere near Soviet levels, but it may be running a little higher than usual. That makes it a good time for a Mister Rogers resurgence. After that, we can start small in our own lives. As Martin Luther King said, “If I cannot do great things, I can do small things in a great way.”

You may find that your physical neighbors and family have all sorts of different opinions, but that it’s no reason to distrust them. Similarly, your hairdresser, grocer, mechanic and banker probably want your trust and repeat business, so you may find that they aren’t out to gouge you.

In his book, Fred Rogers wrote, “There is a close relationship between truth and trust.” Instead of believing politicians, authors and others who sell us paranoid conspiracy theories, remember to, as he recalled his mother saying, “Look for the helpers. You’ll always find people who are helping.” Some small groups with differing views are trying to do just that.

We can reject paranoia and distrust and, as Fred Rogers said, “take the gauntlet and make goodness attractive in this so-called next millennium.” Having the type of country we all want depends on it.