On Memorial Day, we witnessed the George Floyd tragedy in Minneapolis, when a police officer, caught on videotape, kneeled on Floyd’s neck as Floyd strained to say, “I can’t breathe.” Floyd later died.

Then, the more the video of the incident was displayed on national television news, the angrier many Americans got. A nation recoiled, indeed. Wobbled, too.

Next up, a literal firestorm.

Tired of waiting for news of arrests of the four officers involved, disenchanted folk by the thousands took to the streets in Minneapolis and St. Paul to protest. Protests turned into vandalism, then violence, then looting, then fires.

All of that spread from city to city — Los Angeles to Denver to Louisville to Atlanta. All the while in the midst of a devastating coronavirus web of despair that has spawned an economic catastrophe in the United States.

A confluence of crises, for sure.

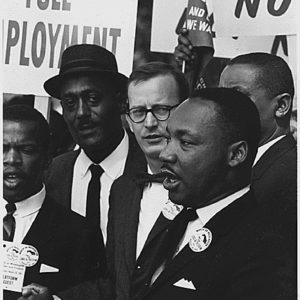

Bernard Lafayette, a key aide in Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s inner circle in the 1960s, knows about such confluences. And crises, too.

In 1967, King named Lafayette the national coordinator for the Poor People’s Campaign, which was King’s last major project before his assassination. On the morning of April 4, 1968, Lafayette met with King at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn., for his last briefing before later boarding a flight to Washington, the site of the economic-rights driven campaign set for May. It was about “Silver Rights,” not just civil rights.

Lafayette was set to head to the Poor People’s Campaign onsite office at 14th and U streets, the cultural and commerce center for black folk in Washington at that time. Soon, Lafayette learned of King’s murder.

Later, we heard a cacophony of police and fire sirens as riots erupted in at least 100 cities around the nation.

Sound familiar?

“Except we didn’t have a pandemic to deal with back then,” said Lafayette, now 80.

No pandemic, but there was much pain and angst, just as today.

Lafayette spoke of symbolism in historic terms when referring to police officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on Floyd’s neck. “His knee was symbolic of the suffering by people of color all around the country for all these years,” Lafayette explained of discrimination in employment, housing, social settings, education, health.

“What’s the difference between a knee on the neck or a noose around the neck?” None, he added. “Because both stop you from breathing.”

There are two statistics to remember here:

— According to a study produced from a partnership by the University of Michigan, Rutgers University and Washington University in St. Louis, police use-of-force is the sixth-leading cause of death for young black men; No. 1 is accidental death, No. 2 is suicide, No. 3 is homicides by others.

— About 100 in 100,000 black men and boys will be killed by police during their lives, while 39 white men and boys per 100,000 are killed by police. This means black men are about 2.5 times more likely to be killed by police than white men.

We have seen protests on behalf of Floyd by a diverse group of demonstrators — old and young, every race imaginable. “And we have many other countries participating,” said Lafayette, who has served on commissions examining the relationships between communities and policing. “We didn’t have that as much back in the ‘60s.”

In the wake of Floyd’s death, we have seen anti-police brutality marches and protests in London; Berlin; Milan; Binnish, Syria; Auckland, New Zealand; Mexico City; Rio de Janeiro; Krakow, Poland; Paris; Copenhagen; Perth, Australia; Toronto.

As for Washington, call it Plywood City. The woodsy smell of plywood permeates the city as carpenters have sawed and hammered away while installing plywood coverings to protect anything glass from ravenous looters. Graffiti scribblings of names such as George Floyd, Trayvon Martin, Breonna Taylor dot buildings throughout the city. On memorials and monuments on the National Mall, too.

By now, we must assume issues of policing will be a core factor come Election Day on Nov. 3, especially for black voters, who represent the heart and conscience of the Democratic Party. Especially from black women.

So, is it mandatory that presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden name a black woman as his running mate?

“I think it would help win his election,” Lafayette predicted, “because there are a large number of black women who are leaders now. And I think they will draw in a number of white women, too. But she must have a platform, a history, a record — and the ability to make change.”

Still, Lafayette warns that Donald Trump remains a formidable foe, despite one crisis after another.

Will Biden’s “you-ain’t-black-if-you-vote-

“Biden was just doing yappity-yap,” Lafayette said. “Find something funny to say. I think he did it to be a little like Trump, get some publicity. You see all of the attention Biden got, didn’t you?”

One last thing, regarding the fight against police brutality, how about WWDKD, as in What Would Dr. King Do?

“If he were alive today, he would be in position to call for leadership in these cities,” Lafayette suggested. “He would be able to establish a national coalition among local ministers, community leaders, government officials, economic leaders, police officials and so forth. The kind of program that would have an impact.”

Similar to King’s impact on the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Call it King’s Clout, as Bernard Lafayette knows firsthand.