Editor’s Note: For another viewpoint, see Counterpoint: The GOP’s Next Big Battle

Most Arizonans have never heard of the Commission on Appellate Court Appointments (CACA), let alone understand the hidden role it plays in defining their state’s politics.

Likewise, most Missourians probably couldn’t explain Citizen Voting-Age Population (CVAP), let alone the way its usage to draw state legislative districts could transform the very nature of representation there for decades.

The politicians like it that way.

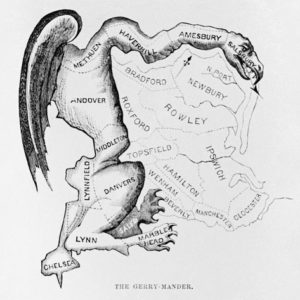

Partisans eager to manipulate elections in these states and others, however, fully grasp CACA, CVAP and other convoluted and wonky ways to tilt district lines to their advantage for the next decade. These tactics might make even the aggressive gerrymanders of this decade look tame.

While most Americans focus on the race for the White House, and Democrats battle to select the party’s 2020 nominee, a quieter, behind-the-scenes game is afoot in state capitals nationwide. The stakes may be more consequential: Every state legislative and congressional district will be redrawn in 2021, after the U.S. census.

When these lines were last drawn, in 2011, the GOP executed a savvy strategy called REDMAP — short for the Redistricting Majority Project — centered on flipping legislatures red during the 2010 midterms, and gaining complete control of the map-making process in key states like Wisconsin, North Carolina, Ohio, Michigan and Pennsylvania.

Then they created new maps with the help of sophisticated new software and terabytes of voter data; they’ve controlled both legislative branches in all five states ever since, and haven’t lost a congressional seat this decade in Wisconsin, North Carolina or Ohio.

More than 59 million Americans live in a state where one or both chambers of the state legislature is controlled by the party that won fewer votes in 2018.

Voters of all political stripes, outraged by this blatant attempt to rig elections, have tried to constrain their own representatives. But even when citizens win landslide initiatives that mandate nonpartisan redistricting, the politicians refuse to listen and simply invent new tricks.

In Arizona, where voters created a bipartisan commission to draw maps, led by an independent unaffiliated with any party, Republicans are now gaming the system so that they can influence the board’s makeup and select its chair.

How? Enter CACA, the state’s appellate court personnel board. CACA is tasked with narrowing the mapmaking commission’s members, and vetting potentially thousands of Republican and Democratic applicants, as well as selecting five finalists for its independent chair.

CACA consists of 15 members, five lawyers and 10 members of the public, and is supposed to reflect the diversity of the state. The state’s Republican governor, however, has simply refused to appoint any Democrats. There isn’t a single Democrat on the board, and no plans to appoint one.

Meanwhile, CACA will begin its work reviewing applicants this year, while the census count is underway. The Democratic members of the commission, in essence, along with the board’s chair, could well be chosen by Republicans.

In Missouri, more than 62 percent of voters backed a 2018 citizen-driven reform package that ended the ability of lawmakers to draw their own legislative districts.

Missouri Republicans decided to rewrite the entire amendment, scrapping the voters’ decision to put a nonpartisan state demographer in charge of drawing political districts, and instead putting the politicians back in charge.

Their plan would also limit the ability of citizens to file suit against these maps as unconstitutional gerrymanders, and change the method by which they are drawn. Right now, Missouri follows the national constitutional standard and draws districts of equal size based on total population.

Republicans want to use citizen voting-age population instead, also known as CVAP, which would allow them not to count non-citizens or anyone under the age of 18. That would have the real world effect of erasing the representational rights of hundreds of thousands of people — and creating districts that skew older, whiter and more rural.

Utah also voted for independent redistricting in 2018.

It’s a one-party state, but Republicans drew lines that allowed them to win nearly 80 percent of the state House with just 62 percent of the vote. Citizens wanted more competition and fewer entrenched incumbents. But now Republicans there have targeted the independent redistricting procedures established by voters and vowed to replace them.

It isn’t just Republicans. Virginia Democrats have pumped the brakes on ratifying a constitutional amendment that would create independent redistricting there.

The plan passed both houses in Virginia in 2019, but any constitutional revisions must pass a second consecutive year — and after Democrats flipped both chambers in 2019, they hold complete control of the process, and, apparently, feel much less urgency about reforming it.

When Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts wrote a 5-4 decision last year that closed the federal courts to partisan gerrymandering claims, ruling them a nonjusticiable political issue, he pointed to the success citizens had in winning reform at the ballot box.

That legislators in all of these states are so brazenly willing not only to ignore the public will — but reverse it entirely, or find new and clever ways around it — shows the weakness of Roberts’ argument. Legislatures often won’t surrender this important power even after voters take it away from them.

District lines are the building blocks of our democracy.

When they’re warped, intentionally, for partisan gain, it distorts our politics. When citizens fight to reinstate fairness, and they’re blocked by their own legislatures or the courts, it calls into question the very legitimacy of representative democracy itself.

Gerrymandering, CACA, CVAP — none of it starts the blood pumping quite like fighting about the presidency. But a president wins a four-year term. The maps these legislatures draw will last for a decade. Both parties will get another shot at the White House in 2024.

These maps? They’ll define our politics in 2031.