Last week, a judge in eastern Oregon enjoined more than 20 of Oregon Gov. Kate Brown’s emergency executive orders closing churches and businesses in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Within hours the Oregon Supreme Court granted an emergency stay of the trial court’s injunction and has since ordered the trial judge to explain his ruling or withdraw it.

If the Supreme Court hears the case on the merits, the question the court will address, presumably, is whether the governor has authority under the constitution and/or the statutory laws of Oregon to do what she has done.

Whether or not the Oregon Supreme Court finds the governor’s executive orders to be authorized, the governor’s initial response to the lower court’s injunction, as reported in Willamette Week, is worrying.

In vowing to appeal the lower court ruling, Brown is quoted as saying: “The science behind these executive orders hasn’t changed one bit. Ongoing physical distancing, staying home as much as possible, and wearing face coverings will save lives across Oregon.”

In support of the governor before the Supreme Court, attorneys for Oregon Nurses Association are reported to have argued: “With no vaccine available, limits on social gatherings, restrictions on businesses, school closures and social distancing practices are the only methods available to combat the virus.”

All of that is probably true, but it has nothing to do with whether or not the executive orders are authorized by the laws of Oregon or prohibited by the individual rights guaranteed in the Oregon and United States constitutions.

The governor’s and the Nurses Association lawyers’ instinctive reliance on science to defend the legality of the executive orders reflects an increasingly widespread insistence that we should defer to science in setting public policy.

Over the last several months we have heard numerous commentators, advocates and public officials declare that we must do what the science tells us in our efforts to combat the pandemic.

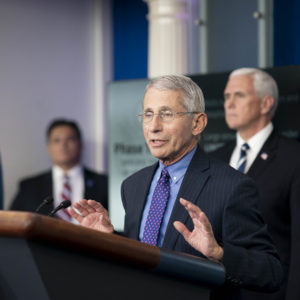

No scientist has been more prominent or had more influence over the last months than Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

In commenting on President Trump’s “Opening Up America Again” plan, Fauci cautioned: “There is a real risk that you will trigger an outbreak that you may not be able to control.”

No doubt there is a risk, and Fauci could probably offer an estimate of how much of a risk. But whether or not to take the risk, whatever Fauci’s best guess says it is, is not a question for science.

It is a policy question that can only be responsibly answered by assessing the health risks from COVID-19 along with many other considerations including the massive costs of closing schools, hospitals and much of the economy.

In weighing all of the many factors relevant to our pandemic response policy public officials should look to science for the best information available. Policy makers should listen closely to Fauci and the thousands of other scientists working to understand the health risks posed by COVID-19.

But if policies are based solely on the best available information on health risks posed by this particular virus, which is what Oregon’s Gov. Brown implied in defending her executive orders, there is a certainty of unconsidered and unintended consequences.

When Brown and most other governors in rapid succession issued closure orders the explanation was almost entirely about preventing spread of the virus and preventing death.

We can fairly conclude, from the absence of contemporaneous mitigation measures, that little consideration was given to the economic, social and other health consequences of a shutdown.

The economic damage is evident to everyone, but there are many other costs. The American Hospital Association estimates that hospitals are losing $50 billion per month.

The Economist reports that “collateral damage” from the closure policies includes the postponement of tens of millions of surgeries worldwide, including 2.3 million cancer surgeries. Deaths and suffering from many causes are resulting from a policy intended to prevent deaths from a single cause.

That is what happens when we defer to, rather than consult, science in setting public policy.

After several weeks of economic and social devastation governors are being forced to weigh the previously unconsidered and unintended consequences of their almost total deference to the immunologists and epidemiologists.

How well they resolve the difficult tradeoffs they are facing will be judged by the voters at the next election. That is as it should be. Whether or not the measures Brown took are legal will be judged by the Oregon Supreme Court.

That, too, is as it should be. Science offers no grounds for resolving either question.