Big Tech Fires Back at Elizabeth Warren’s ‘Break Up’ Billboard

2020 presidential contender Elizabeth Warren put up a billboard in San Francisco yesterday calling for the break up of Big Tech and urging voters to join her antitrust crusade. But a Big Tech trade group representing e-commerce businesses — NetChoice — called Warren’s billboard a “populist rant” without substance.

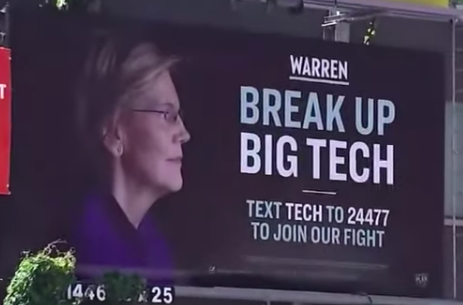

The message on Warren’s billboard is simple and straightforward: “Break Up Big Tech,” with a photo of the Massachusetts senator and a text number to connect to her campaign. As if following Warren’s lead, advocacy group Freedom from Facebook, an offshoot of the Open Markets Institute, flew a banner reading “Break up Facebook! Save Silicon Valley!” over Facebook’s shareholders meeting in Menlo Park, California on Thursday.

“I think what we’re starting to see is weaponization of antitrust law,” Carl Szabo, vice president and general counsel for NetChoice, told InsideSources. “We have over 100 years of antitrust law and enforcement and it’s always done on an objective base. You look at the market and competition and anticompetitive activities and then you do your conclusion. What we’re hearing from people like Elizabeth Warren is they want to move to a subjective test: ‘I don’t like that business, therefore it should be broken up.’ What’s ironic is in their efforts to allegedly protect consumers, many of the calls we’ve heard to break up tech would harm [consumers].”

Breaking up Big Tech divides economists and tech experts. Some dismiss antitrust arguments like Warren’s as unsubstantial, but others say the tech sector is evolving too quickly for the old standards of consumer welfare and antitrust law to keep up.

At an event hosted by the Hoover Institution on May 2, Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) joined economists and tech experts in slamming tech giants like Facebook and Google for systemically buying up their competition, manipulating regulatory policy to benefit their companies, and claiming to protect users’ personal data while selling and sharing it with third-party advertisers to boost the bottom line.

“The biggest monopolies are in the technology sector,” Open Markets Institute Deputy Director Sarah Miller told InsideSources. “We’ve been advocating for the FTC to break up Facebook since the Cambridge Analytica scandal broke, putting some focus on what is now broadly seen as a mistaken decision to allow Facebook to acquire Instagram and WhatsApp among other smaller competitors and companies.”

Lawmakers and economists discussed separating Instagram and WhatsApp from Facebook, but as one economist said, trying to undo a merger is a bit like trying to “unscramble an egg.” But that isn’t stopping advocacy groups from drilling their point home.

“This year we wanted to emphasize that Facebook’s monopoly power is fundamentally warping Silicon Valley and its ability to be a [powerhouse] for innovation,” Miller said. “We’re seeing more innovators and entrepreneurs in the tech sector — most recently Chris Hughes — saying Facebook is a monopoly and really is destroying Silicon Valley as we know it.”

Szabo says proof that competition is robust within the tech industry is the fact that consumers prices continue to fall. Two-day delivery was “unfathomable a decade ago,” he said. Plus, Amazon is only the third-largest retailer and half its e-commerce revenue comes from third-party sellers, so how could it be a “monopoly”?

Some argue that while consumers don’t pay to use Facebook and Google with a monetary price, they do pay too high a price with their personal data. Szabo thinks consumers should just use a different service.

“If you’re using a social network, there’s a multitude of different choices,” Szabo told InsideSources. “There’s Facebook, Twitter, Nextdoor, Reddit. If you don’t want to use one search engine, there are many other search engines. There’s Google, Bing, Duck Duck Go, Yahoo. The market is robust with alternatives and that’s really what empowers consumers.”

But just because there may be other choices doesn’t mean one company should be allowed to get away with harmful or anticompetitive practices, Miller points out.

“Big Tech is a version of Big Tobacco, they’re not necessarily out to make the world a more beautiful place, they’re out to make money,” she said.

Progressives were once very friendly with Big Tech — the Obama administration fostered a cozy relationship with Silicon Valley, resulting in a revolving door between ex-Obama administration officials and Big Tech. Silicon Valley still gives hundreds of thousands of dollars to Democrats (more than Republicans) every year — except Elizabeth Warren.

“Sen. Warren (D-Mass.) has a track record of taking on corporate power, which implies follow-through,” Miller said. “She first talked about tech monopolies back in 2016, she was the first one to talk about it in 2016 and the first person to set forward a detailed plan for restructuring the tech sector. She’s been the pace-setter. Her track record suggests she’s serious about it.”

And that’s what scares Big Tech: other Democratic candidates like Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) and former vice president and senator Joe Biden skirt around the idea of breaking up Big Tech, but Warren said exactly what she’s going to do and her track record with Wall Street following the 2008 financial crisis suggests she won’t back down.

“It does concern us” going into the 2020 race, Szabo said, because he doesn’t think there’s a legitimate antitrust case against Big Tech in the first place. From Big Tech’s perspective, it’s a smear campaign.

“Weaponization of antitrust is essentially handing an enormous amount of political power to whomever controls the White House to attack businesses with whom they disagree,” Szabo said. “Handing over such power to the government should concern all Americans regardless of political affiliation.”