The more I review the United States Census Bureau’s recent report on income and poverty, the more troubled I become. The numbers describing the economic status of Americans are almost all bad. They are especially bad given that we are five years from the end of the recession.

Commentators from both the left and right tend to shrug at these disappointing numbers and say that long-term economic trends starting from as far back as the 1970s condemn our country to losing the battle on income and poverty. But that is not true – we were doing better in 2007 and much better in 2000.

Let’s review some of the disappointing news:

Median household income was no better in 2013 than it was in 2012. In inflation adjusted dollars, it is a startling $4,000 less than in 2007 and $5,000 less than in 1999.

For households with children, median income last rose in 2007.

2013 was the third consecutive year in which more than 45 million Americans lived in poverty. The poverty rate remains two full percentage points above what it was in 2007 and 3.2 percentage points above where we were in 2000. If the 2013 rate mirrored that of 1999, almost 10 million fewer Americans would be in poverty.

Almost 46 percent of children living in female headed single parent families were in poverty in contrast to only 9.5 percent of children in married couple families (down from 2012 when it was 11.1 percent). That improvement for married households is a modest bright spot, confirming once again the advantage married households have over single parent families when it comes to helping their children escape poverty.

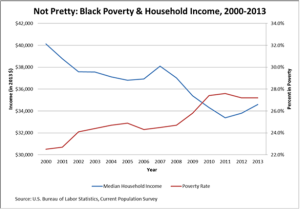

2013 was a bad year for Black Americans. Median income for Black households was $34,598, the lowest of the racial groups reported by the Census Bureau and the gap between Blacks and Hispanics, the next highest group, grew. Black median household income is a shocking 13.8 percent less than it was in 2000 – that’s an almost $6,000 reduction in inflation adjusted income.

The poverty rate for Black Americans did not improve in 2013, and at 27.2 percent, it is 4.7 percentage points higher than in 2000, the year Black poverty hit an all-time low. If this group had the same poverty rate in 2013 that they had in 2000, there would be 1.9 million fewer Black Americans in poverty.

The extent to which people are working continues to be a big predictor of their poverty status. Contradicting a common refrain of some, only 2.8 percent of people who work full time for the full year are classified as poor. And even more notably, over 60 percent of those in poverty did not work at least one week in 2013.

The only good news in this year’s report was statistically significant improvements in median income and poverty status for Hispanics and non-citizens. The real median income of Hispanic households increased by 3.5 percent between 2012 and 2013 and real median income in households maintained by a non-citizen increased by 6 percent.

These improvements are in contrast to no improvements for White, Black or Asian households and no improvements for households maintained by native born or foreign born naturalized citizens. Similarly, Hispanics were the only group among the major race and ethnic groups to experience statistically significant reductions in their poverty rate and the number of people in poverty. Despite these gains in 2013, Hispanic poverty rates are still significantly higher than they were in 2000.

The difference in performance for non-citizens and Hispanics is likely related to their greater improvement in employment status during 2013 – confirming once again that in the fight to raise incomes for the poor and help them escape poverty, working is the biggest key of all.

These discouraging numbers have garnered far too little attention. Half a decade after the Great Recession, and six years into the Obama administration, too many Americans are not earning their way out of poverty because they are not making the transition from public assistance to full-time employment.

Programs intended to be “work supports,” such as housing assistance, Medicaid and Food Stamps, are too frequently delivering benefits to individuals not in the labor force instead of supplementing the earnings of people working at low wages or limited hours. Disability programs are discouraging work for those with impairments which should not stand in the way of employment. And reforms that could get more people working—such as enhancing the Earned Income Tax Credit for childless adults—have yet to be adopted. Low-income Americans are not doing well, and our programs intended to help them get back on their feet have done better in the past and must do better in the future.